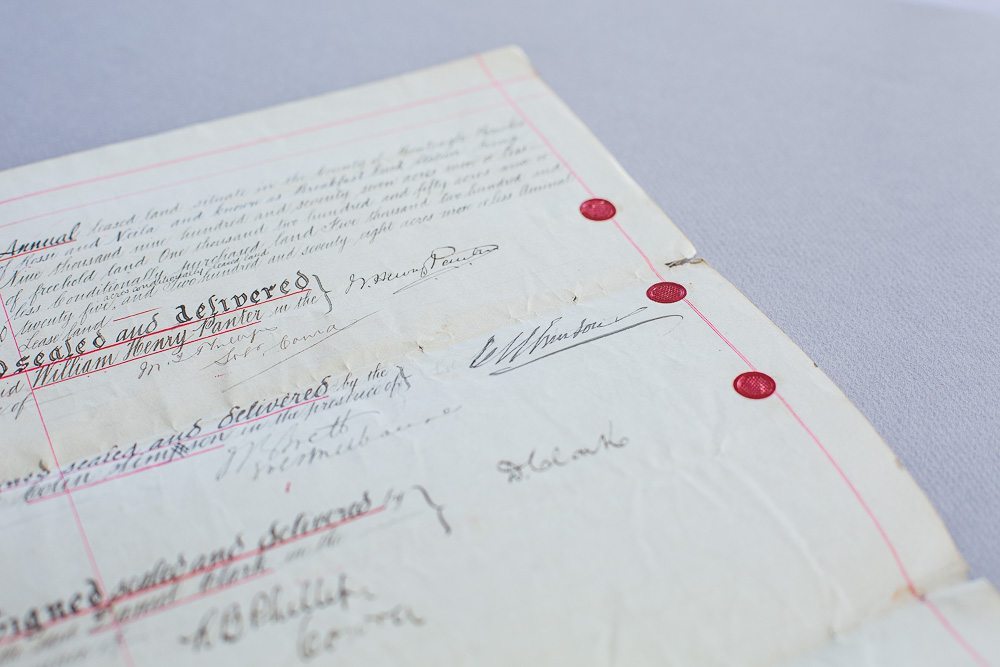

A will is an important document in managing your personal affairs and can, in many cases, be an effective tool in preventing costly litigation for your family after you die. In this case, the estate was embroiled in costly litigation due to handwritten amendments on a will.

There are several requirements that must be adhered to in order for a will to be valid. These requirements are found in the Succession Act 2006 (NSW). In summary, they are as follows:

- the testator must be over the age of eighteen (18) years old and have sufficient capacity to understand its nature and effect;

- the will must be in writing and signed by the testator (or person who is making the will); and

- the will must be signed by the person making the will in the presence of two (2) or more witnesses.

In many cases, family or financial circumstances change frequently, and it becomes necessary to amend your will. In making amendments to a will, it is important to understand that making edits to your will by pen or pencil may not necessarily be valid.

The making of amendments to an existing will by pencil was considered by the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Estate of the late James Sundell [2019] NSWSC 1108.

Mr Sundell executed a will on 9 November 2010. In February 2011, handwritten amendments were made to the 2010 will by his business partner, on Mr Sundell’s instructions, which were initialed in four different places by the testator. The paragraph which was amended related to the gift of shares in a trustee company, which controlled the family assets.

The amendments were made following conversations between the testator and his business partner and were handwritten at the insistence of Mr Sundell, as the amendments were a “simple change” despite his business partner suggesting his will be redrafted or a codicil be prepared.

Section 8 Succession Act provides when the Court may dispense with the statutory requirements for execution, alteration or revocation of wills. Lindsay J in Estate of Moran; Teasel v Hooke [2014] NSWSC 1839 at [26]-[28] held that the question of determining the validity of an amendment was whether at the time of the document being created or (amended at some later time) rests on whether the deceased by act or words showed sufficient intention for the document to operate as their will.

In Sundell, it was contended by the testator’s son that the handwritten amendments were not intended to be legally binding and were only proposed as a strategy to prevent the family assets being exposed to family law litigation.

Sackar J considered the following in determining whether the annotated will of Mr Sundell, whether:

- the handwritten annotations formed part of the will;

- the will should be read in its unannotated form; and

- the deceased intended that the handwritten amendments were to form part of his will.

It was concluded that the handwritten amendments to Mr Sundell’s will were valid and formed part of his testamentary intention.

The outcome, in that case, was not certain. Even though the amends were found to be valid, the estate would likely have expended considerable legal costs in the course of the litigation. If the amendments had been done properly, a lot of time a expense would have been saved.

There are risks in making handwritten amendments to your will. If your circumstances change, you should consult Foulsham and Geddes lawyers who can advise you on how to best reduce any chance of the document being deemed invalid.